The doors swung open wide to Le Royal hotel, and the icy blasts of frigid air beat back the heat outside. Dan Southerland walked through, decades late to his own reunion.

It seemed like a dream he once had, this other existence spent covering the last days before a dogged rebellion took the city, and the country with it.

But the hotel where he stayed while reporting on the Cambodian civil war was still standing. So were many of the other Western journalists, albeit much older now than in those bleary days spent venturing into the unknown to find battles, then returning to send descriptions of them home.

“Don’t you remember me?”

Evenings were spent by the poolside, safe behind the sturdy walls – thick enough, it was hoped, to repel even the most searing rocket fired from an unseen rebel’s weapon.

Last month, the aged correspondents greeted each other in the hotel lobby 35 years after Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge. For Southerland, who covered the wars in Cambodia and Vietnam for The Christian Science Monitor, it was just one of several return trips he has made here over the years.

He had little idea he would come face to face with a forgotten reminder from the past, forcing the darkest memories of his years here to come rushing back.

From across the lobby, Kong Vorn spotted Southerland walking in. The mess of once-dark, tussled hair was cropped shorter now, he saw, and mostly grey.

He walked up and extended his hand. “Are you Southerland?”

Southerland paused. Vaguely familiar, he thought, yet he couldn’t quite place him. Yes, he said, but who are you?

Kong Vorn smiled. It had been so long.

“Don’t you remember me?” he said. “We worked together during the war.”

Southerland stared back in amazement. The recognition sparked before the memories flooded back.

“I thought you were dead,” he said.

A city’s last days

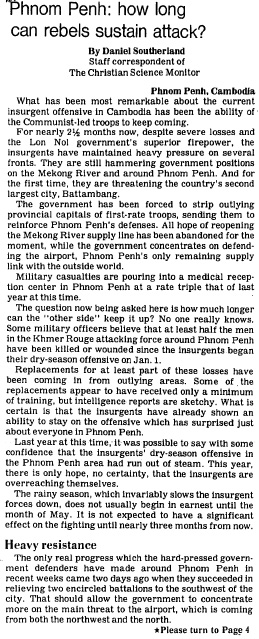

The days grew hotter and the noose slowly tightened. In March 1975, Phnom Penh was a city under siege. Southerland knew by then that it was only a matter of time before the sweltering capital would fall.

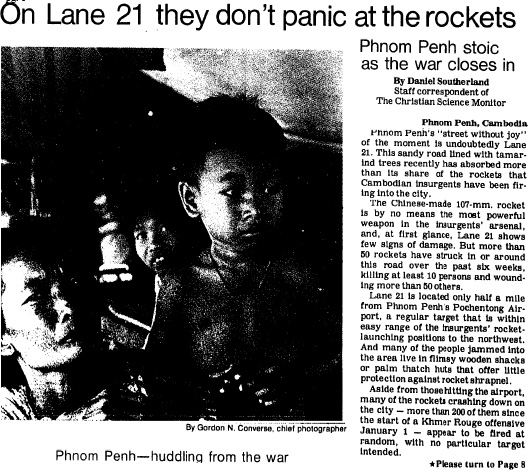

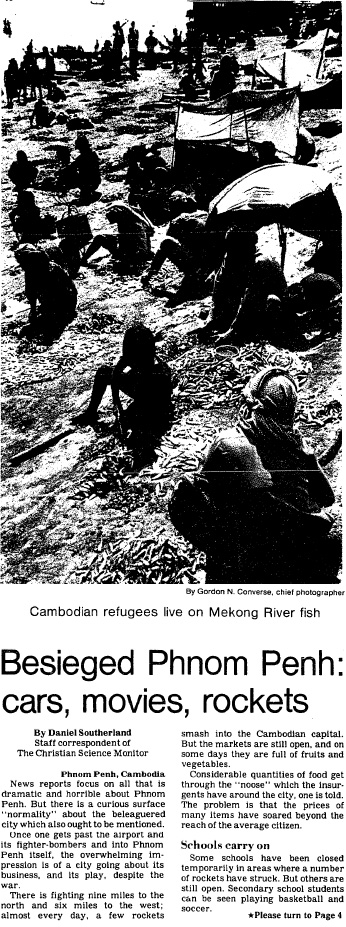

The communist rebels, once confined to the distant countryside, were now a few miles away, bringing the battle to the edge of the city. Rockets whistled through the air and struck with devastating force on a daily basis all through March, and refugees flooded the city as the insurgency wore on.

Yet Southerland saw that the city’s markets were still stocked with fruits and vegetables, the resourceful vendors somehow bypassing the insurgents’ stranglehold up the river. Children played in busy courtyards. Schools and cinemas remained open – though the latter closed early to meet the evening curfew.

But for all the signs of normality, reminders of the war on the edge of town were never far away.

Just a few weeks earlier, shrapnel ripped through a class of primary school students near the Central Market. Southerland watched as hysterical parents rushed to the school, only to be met with guards pushing back against the closed gate. He could still hear the children’s terrified cries.

“The last great illusion in a war built on illusions.”

But as March moved on, so did Southerland.

It had been a long five years darting back and forth between war fronts. He could sense that 130 miles away in Saigon, another city was about to fall. The story of North Vietnamese soldiers bursting into Saigon – that was the story that mattered to his American readers. Southerland realised that he had to choose.

One morning at the end of the month, he packed his bags and said his goodbyes. It was too dangerous now to check in at the airport; the rockets were coming down steadily on Pochentong. The bus from the city centre pulled right up to the waiting airplane.

Already, Cambodia began to subside in Southerland’s memory.

The friends and colleagues he knew here faded too. There were the Khmer journalists, who led him to the simmering war, then pulled him away before it got too close.

There were the desperately optimistic government officials who confided in him, telling him, as if more intent on convincing themselves, that there was still a chance the young republic would hold – even as the rockets fell from the sky; even as the rebels’ stranglehold around the city grew tighter; even though the relief of the monsoons was still weeks away, and with it any hope the rains would drown out the insurgents’ dry-season push.

“If we can change the present leadership,” a cabinet minister told Southerland days before he left, “we are hopeful that we can get more aid and then make another attempt to convince the other side that they must stop the war and talk.”

Southerland had nodded politely and jotted down his notes. But he was doubtful. Any thought of some kind of 11th-hour settlement, he wrote to his editor in his final dispatch from Phnom Penh, “seemed to be the last great illusion in a war built on illusions”.

The airplane lifted and disappeared into the sky. Within three weeks, Phnom Penh had fallen.

April 17

On April 17, the country’s new rulers came to Kong Vorn in his office at the hotel.

Bang! Bang! Bang! A loud knock.

He opened the door to a steely-eyed soldier, rigid in his worn clothes.

So this is the Khmer Rouge, he thought.

There had been an odd calm when the rebels broke through that morning. Kong Vorn watched as the soldiers marched into the capital. For so long they had been a mystery to the average city dweller while the fighting raged in the distant countryside. Now they were here.

There in the confusion of the morning, it felt like a new era for Cambodia. Kong Vorn scribbled notes, preparing to send reports back to his employers at Kyodo news agency in Japan.

We are all Khmer, he had thought as he watched the weary soldiers march through the streets.

The soldier standing before him, however, just fixed him with an icy glare.

“What are you doing?” he demanded.

Kong Vorn paused. “I’m just typing an article,” he said, gesturing over his shoulder. “It’s a story. I’m going to send it to Japan.”

The Americans are about to drop bombs on Phnom Penh, the soldier answered back. “You’ll face serious problems if you don’t leave right now.”

Kong Vorn nodded.

He had been warned about the Khmer Rouge before, when the idea that the ragtag rebels would one day storm into Phnom Penh as victors seemed inconceivable.

“If the Khmer Rouge arrest you, they may never release you,” a North Vietnamese soldier told him years earlier, while he sat captive during a trip with another foreign journalist.

Kong Vorn left his office, shutting the door behind him. A fresh sheet of paper was furled into the typewriter, a few sentences hammered in.

“Phnom Penh has fallen into the hands of the Khmer Rouge,” it read, the ink drying quickly in the room’s hot air.

The killing field

Kong Vorn’s world began to unravel on the road leading north from Phnom Penh.

Columns of cars had jostled with the crowds inching forward. Women laboured with bags balanced precariously over their heads. Men pulled ox carts packed with ratty old suitcases, burlap sacks – anything that could hold a lifetime’s possessions.

“As the knife pierced his neck, the general let out a blood-curdling scream that sent shivers through Kong Vorn’s body.”

He had seen the bodies lying still by the roadside, abandoned. There was no direction to move but forward. The army of refugees inched along, stepping over the bodies.

What is going on? Kong Vorn had thought, glancing at the faces of his family in the rearview mirror of their Mercedes Benz. They stared out the window and didn’t speak.

Days passed as the column of refugees wound its way north. Soldiers pulled Kong Vorn from the crowd and brought the family to a quiet pagoda.

As the days wore on, others were brought in. Other journalists. Former government soldiers. A two-star general.

Early one evening in May, a Land Rover pulled up beside the pagoda. The soldiers crammed 10 people from the pagoda into the seats. Kong Vorn was the last to climb in.

They drove in silence towards the jungle. Dark storm clouds filled the sky and the rains began with a crackle.

When the vehicle stopped near a clearing, the ground was drenched and the daylight was almost gone.

Ragged Khmer Rouge soldiers met the group and ordered them to undress.

They grabbed the clothing, then turned the men roughly around, tying their hands behind their backs.

Kong Vorn watched in horror as the knives flashed. The sound of thunder rumbled overhead.

The two-star general was the first to go. A soldier grabbed him by the shoulder and stabbed him in the neck, again and again.

As the knife pierced his neck, the general let out a blood-curdling scream that sent shivers through Kong Vorn’s body.

“He scrambled towards the trees, naked from the waist down, his hands bound together behind his back.”

Run, he thought.

Kong Vorn pivoted and kicked the soldier behind him in the knees. The soldier buckled to the ground and Kong Vorn took off.

80 metres to the jungle, he saw.

The rain poured down.

“Stop!” the soldiers shouted. “Stop now!”

70 metres.

He scrambled towards the trees, naked from the waist down, his hands bound together behind his back.

50 metres.

He could hear the soldiers’ footsteps in the wet grass. He felt the thump of his own heart beating, pounding in his ear.

20 metres.

“Stop!” Their voices more distant now.

10 metres.

Kong Vorn crashed into the darkness of the jungle floor.

He heard only the thunder rumbling overhead. The rain tumbling heavily onto the trees above him. His own heartbeat, pounding. His laboured breaths, gasping for air.

The soldiers calling out, their voices coming near and then falling away. Their heavy footsteps, landing first with a thud on the underbrush, then fading into the rainfall.

Refugees’ stories

Southerland stared in disbelief at the bleary-eyed refugee in front of him.

The farmer claimed he fled after he was ordered to bury the bodies of former government soldiers. There were 400, maybe 500 bodies, he insisted. He saw some who had been tied and then beaten with pieces of timber.

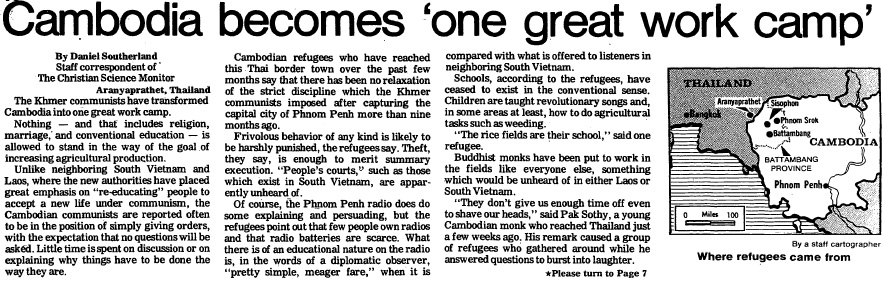

It was 1976 near a Thai border town that was bulging at the seams, filled with refugees streaming in from Battambang.

Their tales of life under the Khmer Rouge, now almost a year in power, were grim. Religion, commerce, education – all banished. Executions delivered with little deliberation. Stories of villagers driven away, never to be seen again.

Another refugee said his entire family – wife, children, parents, five younger brothers – was beaten to death.

Southerland dutifully recorded the horrific stories. He turned to a colleague. “What do you make of this?” he asked.

“What we have seen so far falls short of a central government policy to exterminate whole classes of people.”

Could it really be true? Could this be happening across the country?

Other foreign observers, too, piecing together their own pictures of the now-secluded country from the refugees who fled it, weren’t sure how much they could believe.

“What we have seen so far falls short of a central government policy to exterminate whole classes of people on a nationwide basis,” one diplomat told him before the trip.

But the stories were so detailed and so consistent, Southerland thought.

He finished his interviews and plugged out the story. The refugees’ incredible claims were tempered by cautious caveats – an uncertain report of the bloodshed unfolding within the Kingdom.

“The Khmer communists,” he wrote, “have transformed Cambodia into one great work camp.”

Southerland wouldn’t realise until years later how much of an understatement it was.

Opening a school

In a quiet courtyard off a side street in Phnom Penh, Kong Vorn sat this month recalling his memories of a time in which his country was ripped apart.

While Southerland was interviewing refugees along the Thai border, Kong Vorn was living a lie as an illiterate peasant, having walked to his wife’s homeland in Prey Veng. Eventually, his wife and daughter made their way there too.

“Never say anything about who you are,” he had told them in a quiet moment. “Obey their words. Never question anything.”

Kong Vorn’s memories are typed out on three orderly sheets of paper so he never forgets.

“To be calm is to live. To complain is to die,” he said. “So we never had any questions. It was better not to say anything. That is what kept us alive.”

Prey Veng was one of the first areas to fall when the Khmer Rouge collapsed with the Vietnamese invasion in 1979.

Kong Vorn and his family received permission to move to Japan shortly after. Already in his 40s, he started a new life there, working for an electricity company. His granddaughter gave birth to three children.

They stayed there for 17 years, until Kong Vorn retired and returned to Cambodia.

Today, Kong Vorn lives off his Japanese pension and raises funds for his NGO, the Cambodia Education Assistance Fund. The organisation has constructed a school in Prey Veng, where he waited out the Khmer Rouge rule in fear. Almost 1,000 students attend classes for free.

The Khmer Rouge despised the educated. Kong Vorn survived because he pretended to be illiterate.

“Those people caused big problems for our society,” he said. “In order to stop these atrocities from happening again, everybody has to be educated.

“Cambodia has so many people who are uneducated. So many people who farm for a living and do not go to school. So to develop the nation, we all must learn.”

Last month, Kong Vorn saw an advertisement for the foreign journalists’ reunion in Phnom Penh. He thought he recognised Southerland’s name.

He remembered the soft-spoken American journalist born just a month before him in 1937; he remembered how he treated him and other Khmer journalists as equals.

“I can’t describe how happy I was to see him again,” Kong Vorn said. “We had been away from each other for so many years. It has been so long.”

The pair snuck away from the reunion to talk. Family pictures were shown. Memories were exchanged. Plans were struck for future visits. Still, Kong Vorn knew, so much time has already passed.

“I wish we had met again many years ago,” he said. “Now, I’m already more than 70 years old.”

Memories resurface

For Southerland, who watched from afar as Cambodia shut out the outside world and then imploded, the memories are just below the surface.

He laughed in delight last month as the memories of Kong Vorn and others returned. But the elation was quickly followed by a feeling of guilt. As the Khmer Rouge regime fell and the country slowly opened up again, Southerland never thought to look for his former colleagues. They were English-speaking professionals who worked with foreign journalists; he thought there was no way any of them had survived.

“It’s kind of embarrassing,” he said. “I just assumed everybody I knew was dead.”

The memories rushed back the longer he spent talking. Anything more than a superficial conversation with someone who lived through the Khmer Rouge years still brings feelings of shame and anger. He finds it difficult to look at the vivid black and white photos that tell stories of the era. He is still reminded of the rocket that tore through that primary school in Phnom Penh.

“The worst thing you can hear,” he said, “is the sound of children crying. It almost seems like a dream now, but I’m sure it happened.”

He went back to find the school a few years ago, looking for signs of the past in the now-bustling neighbourhood. No one remembered.

“I was like a lost soul, distressed to find that no one remembered anything,” he said.

Someone had to explain to him that few of the people who lived there before the Khmer Rouge had returned.

The old photos also stir up the anger he tried to suppress as his plane lifted away from Phnom Penh 35 years ago.

Southerland still remembers witnessing the aftermath of some of the US military operations into Cambodia during the war, what he later decided were part of his own government’s callous campaign to provide cover for its eventual withdrawal from Vietnam.

He remembers walking into a village that had been half flattened by American fighter jets hours earlier.

The only casualties were innocent civilians.

“You journalists can see the problems with your own eyes,” an old man told him, one of many huddled for shelter near a shattered pagoda.

“Most of the American people cannot see with their own eyes, so your government gets away with lying to them.”

Southerland kept a small piece of wood from the pagoda on his desk for years after.

“Just to remind me of what happened,” he said.

This story was published in The Phnom Penh Post.